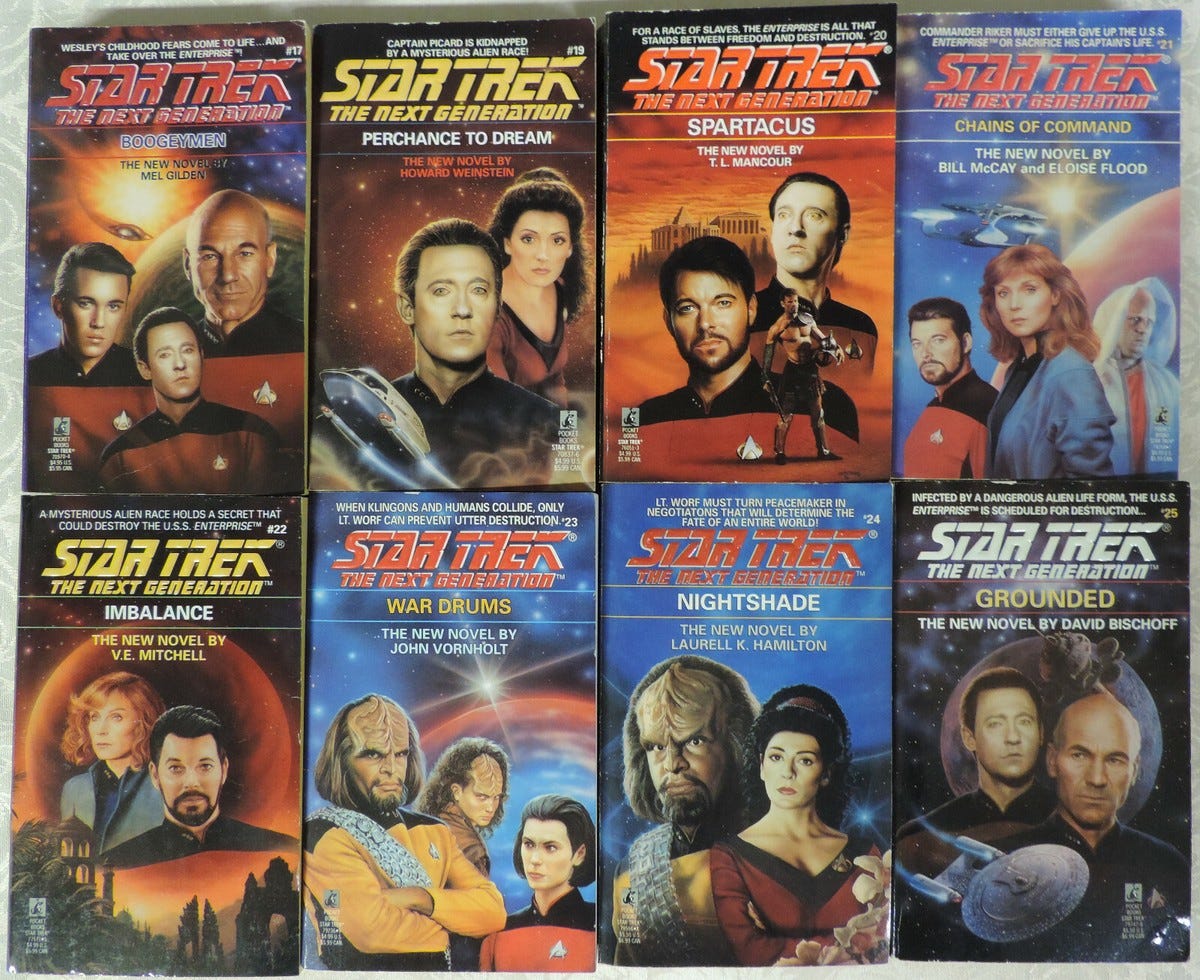

This past week, I was travelling, and for me, travelling means science fiction on a plane! I’ve spent many happy hours on international flights plowing through Culture novels or dwelling with Adrian Tchaikowsky’s sentient spiders, but the bulk of my travel reading in the last ten years or so has been Star Trek novels. On a recent podcast, I blurted out that I had read 200 Star Trek novels, which I immediately realized was an exaggeration, so after finishing my travel reads, I decided to attempt to tabulate—and more specifically to track my progress in the novelverse, which is the vast continuity that the novel authors developed following the cancellation of Voyager. As I write in my book, the (quite reasonable) expectation that no further “canon” material from this era of Star Trek would be forthcoming allowed them to carry the story of the 90s series forward in increasingly complex and ambitious ways. Only with the debut of Picard was the novelverse officially preempted, which led them to officially write the novel continuity out of Star Trek history with a concluding trilogy entitled Coda.

Using the most recent (and, if I judge the creators’ contempt for the final novels in this continuity, likely the final) version of the frankly intimidating Litverse Flowchart, I put an X next to all the books I had read. You can see the result here. According to my ocular scan, I placed 76 X’s—and surprisingly, I often remembered what each novel was about, despite their studiously vague titles. Adding the three Coda books, that comes to 79 books within the novel continuity (or pre-continuity books that novelverse authors lean heavily on).

That’s a lot of X’s. But I estimate that it represents maybe a third of the entire vast continuity—and there are whole tranches of this world (particularly DS9 material, which I will probably get around to eventually, and Mirror Universe stuff, which I probably won’t) that I haven’t even touched. If you click through, you may also notice a lot of skipped novels within broader series. What is less evident is the order in which I read them, which didn’t even approximate chronological order. Instead, I jumped around based on some combination of my interests and the vagaries of the publishers’ monthly 99-cent Kindle deals—which means that my Star Trek novel habit, which is by any measure one of my primary forms of entertainment, has cost me probably $20-30 a year.

In addition to novelverse titles, I have also checked in on the classics and the tie-ins for the more recent shows, which easily brings my total above 100 (though nowhere near 200). But my heart really belongs to the novelverse, in part because of its sprawling endlessness. There just isn’t another ongoing fictional project like it, arguably other than the Star Wars novels (which have themselves been “de-canonized” by the artistically inferior sequel trilogy, just as the novelverse was “de-canonized” by the abyssmal Picard). It is admittedly intimidating to look at the chart, but you really can start anywhere, because the authors always provide a potted summary of any background you need to know about (from TV episodes or previous novels). In fact, they sometimes do this so much, and so inelegantly, that it can be maddening if you’re reading a particular series in rapid succession. But it does help preserve the episodic nature of most individual novels, and the relative self-containedness of most of the mini-series within the continuity.

One reason I wanted to take stock after this particular airplane Star Trek reading binge was that I had finally dipped into the series that really founded the novelverse project: A Time To… (2004). So named because each book takes its title from the well-known passage of Ecclesiastes (or the well-known song from every montage of events from the 1960s), the series attempts to account for some unexpected plot developments in the Next Generation films Insurrection and Nemesis—most notably Worf’s apparent demotion from ambassador back to tactical officer and Wesley’s appearance in human form at Riker and Troi’s wedding. These thin reeds of nitpicking lore somehow gave rise to a nine-book series (initially planned for twelve, to be released rapid-fire, one per month) that radically reset the Next Generation characters’ status quo and set the stage for new, largely independent plot developments within the novels.

The reason I had never gotten around to them before is that they never pop up in the monthly deals. Asking around among other novel fans, I got the impression that it may be because they sold poorly initially—reportedly ebooks are only discounted like this if they earned out their advance. And despite my unparalleled stamina, I was also intimidated by the prospect of signing up for nine novels (which would represent probably a year’s worth of reading at my usual pace). Thankfully, my sources indicated that the first six books were skippable and I should simply jump ahead to David Mack’s installments (A Time to Kill and A Time to Heal—his debut full-length Trek novels) and then read the ninth and final novel (A Time for War, A Time for Peace by veteran Trek novelist Keith R.A. DeCandido) to get a sense of the whole series.

As I expected, the first six books were relentlessly resummarized, so I think I have a fair view of the overall trajectory of the series. And it is a grim one—we witness the Enterprise crew enduring one failure and humiliation after another. The triggering event is a battle in which they face an opponent who can mimic other ships perfectly and Picard, trusting Data’s assessment, fires on what turns out to be a real Starfleet ship, destroying it and killing all aboard. The incident stains Picard’s reputation, leading to mass transfers and difficulty recruiting quality replacements, and results in the forcible removal of hard-won Data’s emotion chip.

When we join the crew in Mack’s A Time to Kill—a strikingly accomplished first effort by the author who will turn out to be the primary architect of the novelverse—they are in the middle of a tense stand-off above the planet Tezwa. This seemingly minor planet, filled with bird people, had taken on unexpected geopolitical importance when Federation President Min Zife and his Dick Cheney-esque apparatchik Koll Azernal cut a deal to place advanced Starfleet weaponry on the planet’s surface in a desperate bid to cripple the enemy fleet during the Dominion War. This move had to be kept secret because Tezwa was located near the border of the Klingon Empire and arming it would be a violation of the Federation’s crucial alliance with the Klingons (which had already briefly been suspended in the lead-in to the Dominion War).

Unfortunately, the leader of Tezwa, Kinchawn (again, a bird-person), got a little too big for their britches and decided to take advantage of the situation by attacking some Klingon worlds in a bid for expansion—secure in the knowledge that they could mass-murder any Klingon fleet using their huge Starfleet guns. This desperate gambit blows up in Kinchawn’s face when the Enterprise crew disables the weapons at the decisive moment and the Klingons decimate the surface of the planet. Full-scale genocide is only prevented when Picard gets Ambassador Worf to steal the command codes for the entire Klingon fleet so that he can forcibly halt their attack without further loss of life.

This presidential treachery underlying all of this appears to be entirely Mack’s own invention (though I can’t know 100% for sure without reading through the six other novels)—part of Star Trek’s broader obsession of “inside jobs” during the Bush years. The Bush reference also serves him in good stead in A Time to Heal, where Picard is heading up a Starfleet humanitarian force tasked with rebuilding the planet. The heroes of the most optimistic Star Trek series find themselves bogged down in a brutal counterinsurgency, complicated by ethnic divisions among the Tezwan bird-people (I keep bringing this up to emphasize that they could never do this in a live-action production). There is suicide bombing galore and many mass-casualty events. An author insert, Lt. Peart (named after the drummer and lyricist for Mack’s favorite band, which is unfortunately Rush), finds himself so devastated by the experience that he resigns from Starfleet to seek a new life. Perhaps he decides to become a novelist, off-camera?

Once Picard learns of the president’s malfeasance and lets Starfleet know, they strongarm him to resign—while keeping the whole affair top-secret, lest it lead to a devastating war with the Klingons. For good measure, they allow Section 31 to quietly murder the president and his main collaborators. (In his final scene in particular, the president comes across as a George W. Bush-esque imbecile, naively accepting the rationale for his resignation and overruling Space Cheney.) This becomes the original sin of the entire novelverse, which is only fully resolved over 15 years later in Mack’s novels Control (where Section 31 is finally dissolved and its crimes made public) and Collateral Damage (where Picard faces a court martial over his complicity with the president’s forced resignation and death; spoiler alert, he is aquitted).

Taken together, Mack’s two novels are a bold statement of intent. Building on the legacy of Deep Space Nine (whose follow-up novels had already introduced their own, still largely self-contained continuity), Mack wants to show that Next Generation can handle war and loss and intense political intrigue. It’s no wonder that they turned to him again and again to script the most decisive moments of the novelverse. It also established him as one of the most competent tie-in writers in terms of capturing the authentic voice of characters, avoiding turgid prose, and delivering convincing action scenes that are genuinly tense (including a simultaneous operation among six different away teams to disable the illicit weapons before they fire on the Klingons). Sometimes he arguably pushes the grimdark too far—and I find the theft of the command codes for the entire Klingon fleet to be just a bit too much, especially in the middle of a plot where they are ostensibly trying to avoid angering them into war—but he brings an energy and ambition to the task that more established authors may not have had.

DeCandido’s finale to the abbreviated series—which is itself abbreviated, as it is the only installment not to be divided into a paired duology—is a bit of a comedown after Mack’s intense installments. This last novel devotes itself primarily to figuring out how to get Worf out of the ambassador job and back on the Enterprise, which he achieves by staging a scenario where Klingon terrorists take over the Federation embassy and Worf single-handedly defeats them through sheer badassery. Realizing that he prefers badassery to diplomacy, Worf retires and returns to Starfleet. In my mind, this is the kind of plot development that could be handled in a sentence, rather than, say, one-third of a novel. DeCandido also spends an absurd amount of space on the fate of the Khaless clone who was installed to the ceremonial post of Emperor in a particularly ill-judged TNG episode.

The most enduring development from the end of the A Time To… series is the snap presidential election following the evil president’s resignation. Here we meet Nanietta “Nan” Bacco, governor of a Federation planet and sassy Italian grandma, who will be the president for most of the events of the novel continuity. She is probably the most-loved “novel-only” character of all time, and the only “novel-only” character to star in her own book, namely DeCandido’s follow-up, the fan favorite Articles of the Federation, which is basically “West Wing in space.” I love the character as she develops, but her introduction here is somewhat held back by DeCandido’s imperfect execution of “witty banter”—a vice that negatively affects the interactions among the Enterprise crew as well. Overall, DeCandido does not do as good a job of capturing the authentic voice of the characters, and his decision to make Worf’s son Alexander a point-of-view character for long stretches of the novel is particularly ill-judged as there is no way to wring a coherent personality or thought process from Alexander’s scattered plot trajectory.

Still, I found the novel to be an enjoyable, if at times absurd, plane read. I particularly enjoyed reading the acknowledgments, which credited David Mack with vastly improving the tail end of the A Time To… series and, perhaps more notably, displayed palpable enthusiasm for upcoming novel projects (including Articles of the Federation and the start of the Titan series following Riker’s long-delayed first command). Whether this series sold well or not, the odd little tribe of Star Trek tie-in novelists knew they were building something new here and they were excited to share it with the fans. It made me nostalgic for this early stage of the novelverse, particularly Article of the Federation, which I may go so far as to re-read!

What also struck me about DeCandido’s novel was how often he seemed to refer back to events I did not recognize, which I inferred must be from then-recent Next Generation novels that have not been memorialized on the chart. In other words, even as I was closing the circle on the most important events in the novelverse, I learned that there is yet another tranche that I have not dipped into. It truly boggles the mind. With any luck, some of those forgotten one-off installments will come up on the monthly Kindle deals.

I think I am also starting to realize i need to start checking the monthly kindle books for cheap trek books. I'm just finishing a couple of the TOS novels I got for cheap that way. Also finally read Imzadi, a cover I have been seeing for years but never actually read. Much better than I expected tbh!

Speaking of TOS, do you dabble in the TOS stuff at all? Or mostly TNG/DS9? I'm enjoying the TOS stuff, but they definitely lean hard into all the tropes of 60s romance and adventure, for better or worse.

Ha I’ve been meaning to ask you if the DS9 continuation books were worth the time but never mind I guess